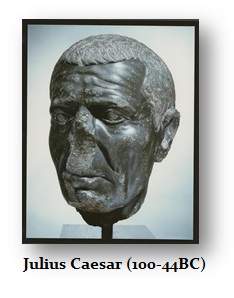

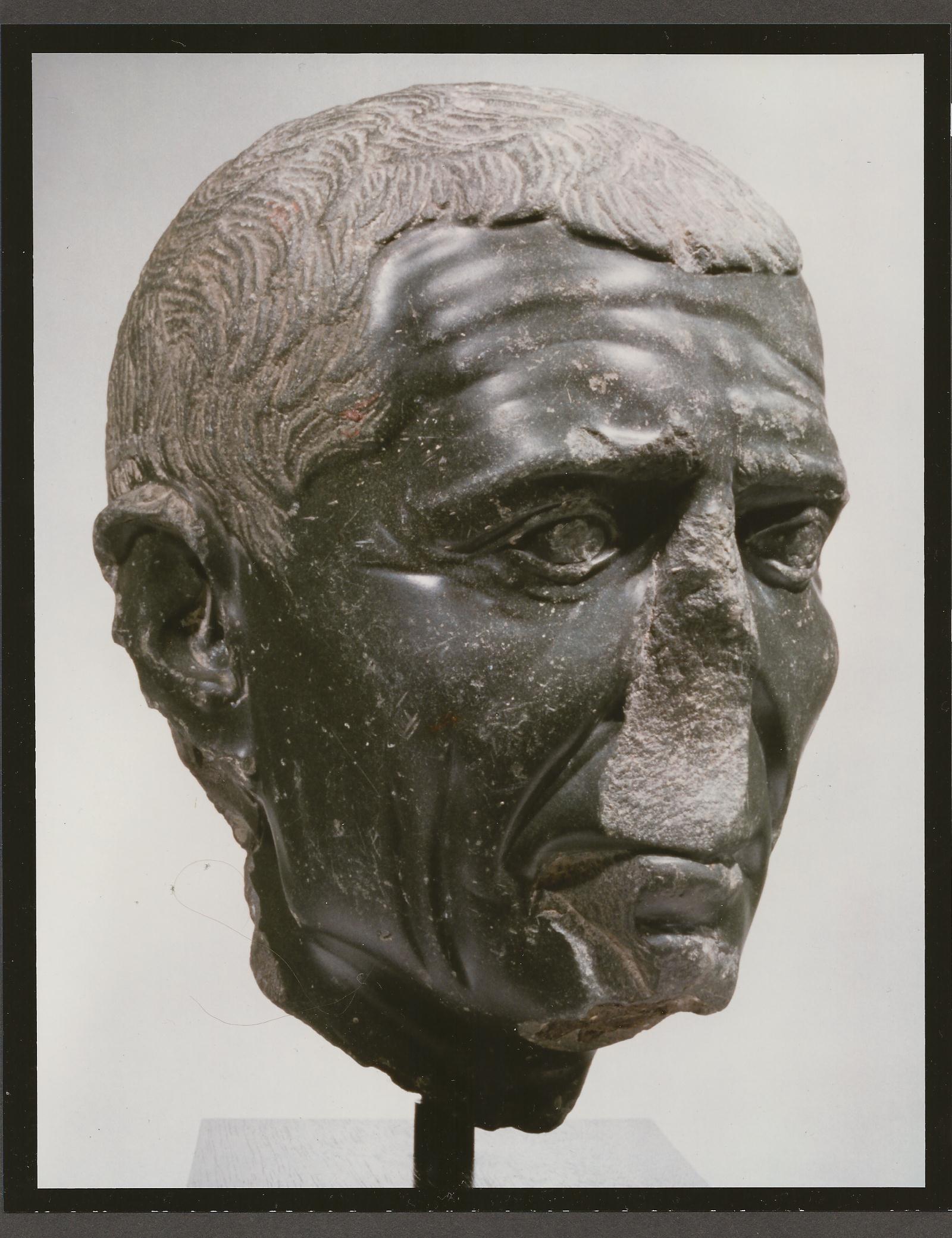

The black basalt bust of Julius Caesar is more likely than not the one commissioned by Cleopatra herself. We know that Cleopatra had built an elaborate shrine, or Caesareum, to Julius Caesar opposite the harbor of Alexandria. He was the father of her son and she clearly was politically driven to take Rome by marriage. After all, after Caesar’s assassination, she turned her political designs to Marc Antony. There are numerous coin issues showing her portrait with that of Antony, demonstrating her political designs.

In this heroon created by Cleopatra, there once stood an image (simulacrum) of the deified Julius Caesar in black basalt — a stone reserved for people of the highest rank. After the death of Cleopatra, this shrine was dedicated to Augustus, and therefore became an Augusteum. Unfortunately, we do not know what other images of members of the Augustan and Julio-Claudian house were set up here. However, since this heroon was rededicated to Augustus, a portrait of Augustus was undoubtedly added.

It was common practice to set up images of other members of the imperial family in such shrines. A portrait of Augustus’ niece, Antonia Minor, has also survived and was defaced in the same manner as the bust of Caesar, which was known to have been in southern France, and was a likely candidate for honoring in a rededicated Augusteum. Of course it cannot be determined with certainty whether the two basalt portraits were created at the same time, or whether a portrait of Antonia Minor along with other (now missing) portraits of family members were added shortly after the rededication of then creation of the Augusteum. Nevertheless, this black basalt portrait of Julius Caesar was the first established by Cleopatra herself, obviously for political reasons.

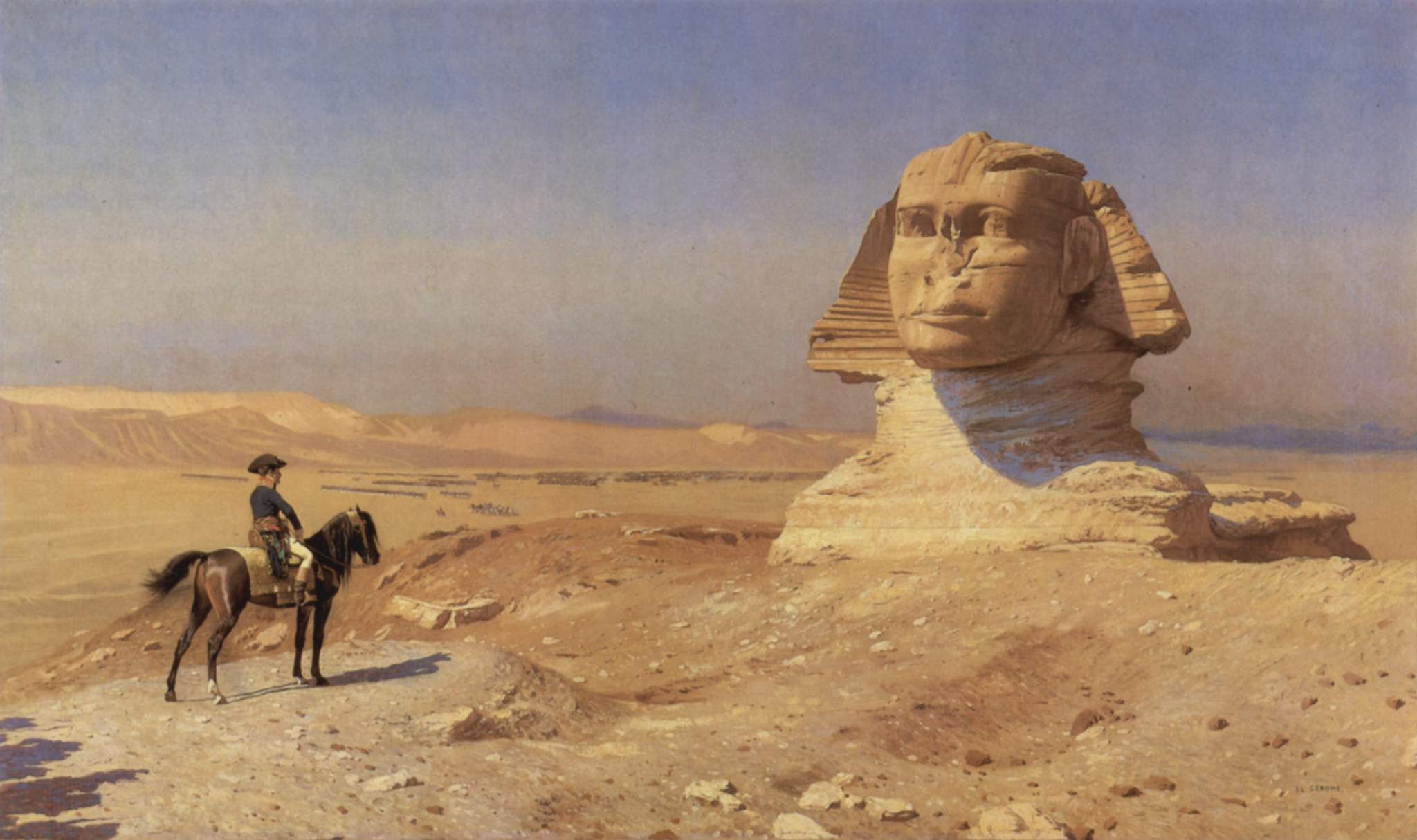

Nevertheless, it does seem that the two surviving black basalt busts of Caesar and Antonia were part of the same imperial portrait group because of iconographical considerations: the distinctive and relatively rare material, the size, and similarity of workmanship (undoubtedly produced by the same workshop), and the nature and degree of damage. Additionally, their reported association with the same collection in Southern France that suggests that they were brought back to France during the Napoleonic campaign.